Workforce planning: Industries at risk

With a rapidly growing number of organisations adopting cutting-edge innovations like cloud computing, artificial intelligence, machine learning, and data analytics, the skill sets that industries now require look very different from those of even just a year ago.

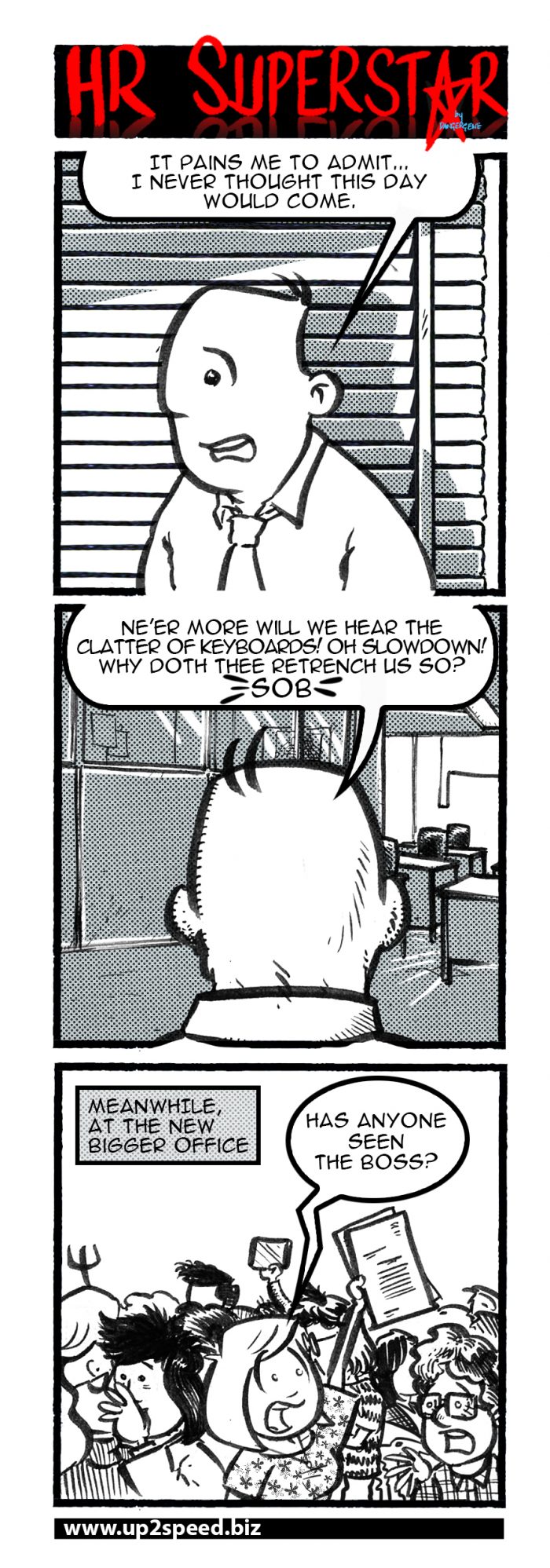

This is especially true for traditional industries like aviation, retail, shipping, finance, and manufacturing, which are now bearing the brunt of technological disruption. It is evident by the number of layoffs and lukewarm hiring pace in the first quarter of this year alone.

“There hasn’t been a lot of massive hiring in the market in the last one year,” Foo See Yang, Managing Director, Kelly Services Singapore, tells HRM Magazine Asia.

“What’s happening with all these technology adoptions is many companies are conducting internal restructures and redesigning jobs right now.”

Singapore’s manufacturing sector, for example, saw total employment drop by 4,300 in the first quarter of 2018, according to the Ministry of Manpower’s First Quarter Labour Report.

Like manufacturing, the construction sector had seen total employment shrink for five consecutive quarters, between 2016 and 2017.

Similar trends have also been observed across the Asian markets over the last 12 months. In Thailand, the manufacturing Purchasing Managers’ Index hit an eight-month low of 49.6 in July 2017, according to Nikkei. A reading below 50 indicates contraction, while a reading above 50 points towards expansion.

The impact of Industry 4.0

To really understand what’s happening across the different industries and markets, Foo says it is necessary to look beyond the numbers.

“I would not simply look at it as just a cutting of jobs, but the reasons behind it. These layoffs are happening because companies are replacing old work models,” he says. In fact, Foo attributes the tepid job market to the “reinvention” and digitalisation of the economy, and not an economic downturn.

Retail is a prime example of a sector that has suffered in recent years as a result of changing market conditions. It is no secret that e-commerce has slowly been eroding the pie of brick and mortar stores since the early 2000s. And based on growth rates in the last two years, analysts are predicting that e-commerce will overtake offline retailers much sooner rather than later.

The demise of several household names across Asia, and the rise of online outlets like Alibaba, are further proof of the offline sector’s steady retreat.

In February this year, US clothing retailer Gap ceased all its shop operations in Singapore and Malaysia on the back of falling sales. Three months later, Hong Kong fashion brand Esprit also announced it would be exiting the Australian and New Zealand markets for good.

Meanwhile, Chinese internet group Alibaba announced in March this year it is injecting an additional S$2.6 billion into the Singapore-founded Lazada; US marketplace pioneer Amazon launched local services across Southeast Asia; and new players like Shopee (backed by The Sea Group, which also owns Garena) continue to expand their footprint throughout the region.

“Retail is generally very competitive due to online options like Zalora. It’s no secret that we traditional players are feeling the heat,” says Zen Tan, Senior HR Executive at Big Box Singapore.

“We (Big Box) were trying to fight with the big players, but we realised it was not working out, so now we’re in a transition phase.”

The competition has forced Big Box, a factory outlet concept mall to replace parts of its product offerings with options promising more commercial viability.

The fashion and lifestyle department, for example, has been superseded by a furniture section and specialised stores selling imports that are not available anywhere else in Singapore.

This has had a negative impact on some employees. Tan says HR will typically redeploy individuals to new roles where possible, but reveals that the business has “had to let some people go” while it “repositions” itself.

It has recently been announced that Big Box’s parent company TT International has put the business up for sale, though the reasons for the sale have not been revealed.

Hiring for specialised roles

Between 2011 and 2016, Singapore Airlines shed 12% of its pilots. Then, following a S$138 million net loss in the fourth quarter of 2016, CEO Goh Choon Pong announced a three-year transformation plan that will reportedly involve a significant number of further retrenchments.

The plan, Goh wrote in a company newsletter, is aimed at helping the airline to regain its “market and financial leadership”.

Industry observers say the layoffs could indicate that there is trouble in paradise, but in this instance, it’s more a case of passé roles being phased out and redesigned to make room for high-value roles and functions.

As Ashish Ashdir, Air Asia’s Group Head of Global Talent Acquisition, shared at a recent LinkedIn business event, redeployment is certainly a top priority for airlines now, as they look towards reskilling their people with the necessary competencies for their next phases of growth.

“Future-proofing is not just a concept. Everyone recognises that this is the only way an organisation will survive,” says Ashdir.

And as an organisation that “never lays off people”, Ashdir says the focus is now on upskilling and coaching employees so that they become agile and prepared for any uncertainties, while equipping them with technical skills at the same time.

Ashdir is tight-lipped on Air Asia’s recruitment volume for the past 12 months, but says that “in this transition phase, a bulk of hiring will be for digital skills”.

With the company now on the cusp of rolling out an HR chatbot and other high-tech platforms, hiring for specialised roles, rather than hiring in bulk, is the order of the day.“These are not skills of tomorrow, these are skills of today, and we need to prioritise them,” says Ashdir.

Retrenchment as a last resort

Arguably, nowhere has restructuring been more widespread than the finance industry.

In Australia, the top four banks – namely National Australia Bank (NAB), the Australia and New Zealand Banking Group (ANZ), Commonwealth Bank, and Westpac – are said to be slashing their workforces by a combined 20,000 employees this year.

In September 2017, NAB announced it would cut 4,000 jobs over the next three years.

And as part of ANZ’s reorganisation of its Australian corporate division to become more agile and startup-like, as well as its withdrawal from Asia, some 5,256 staff members were let go between 2016 and 2017.

Elsewhere, former Deutsche Bank CEO John Cryan told The Financial Times at the end of 2017 that the organisation employs too many people, before adding that the introduction of machine learning and artificial intelligence could potentially halve the 97,000 workers currently on its books.

Jeremy Broome, Regional Head of HR for Deutsche Bank in Asia-Pacific, echoes his former boss’ thoughts, saying that technology will have a “huge impact on the banking industry in the next two to four years”.

_____________________

“If you’ve got a relatively long lead time of a few years to predictively understand how the skills demand is changing, then you are able to plan your pipeline effectively.”

– Jeremy Broome, Regional Head of HR, Deutsche Bank Asia-Pacific

_____________________

Broome says job cuts are inevitable during this transition period, but at Deutsche Bank, the first step is to redeploy people, not retrench them. “We redeployed 40% of roles that were at risk in 2017,” he shares.

The next focus for HR, Broome adds, will be in determining what jobs will be automated, what jobs will remain, and what training and development will be needed in the new job landscape.

“The interesting thing for HR is around the speed at which that change is happening,” Broome tells HRM Magazine Asia. “If you’ve got a relatively long lead time of a few years to predictively understand how the skills demand is changing, then you are able to plan your pipeline effectively.

“But with the rapid speed at which change is happening today, the extent to which you as HR can predict development needs is much harder now.”

Why functions are changing

The insurance industry, which is on the road to recovery after a slow 2016 and 2017, is also feeling pressure from the proliferation of intelligent machinery.

Angie Ng, Chief HR Officer, Manulife Singapore, says although the financial services sector is still more traditional and “behind” the banking industry, many insurers are already looking at what processes can be automated.

Parts of policy underwriting, for example, can be performed by artificial intelligence. This then frees up underwriters to focus more on value-added tasks like cognitive behavioural analysis of customers. Customer service chatbots will likely also replace the need for face-to-face interactions.

But even as the roles for humans change, Ng agrees with Broome and Air Asia’s Ashdir that “there’s no need to lower headcount when you can redeploy roles”.

Where skills cannot be built, Ng says the company is “looking for people who can change our organisation and industry”.

With so many industries disrupting their work models just in these last two years alone, it seems that this is only the start of more reshuffling to come. It also appears that as we move towards 2020, companies will continue hiring and firing strategically, so as to remain relevant and competitive in a dynamic digital economy.

As for jobseekers, Ashdir puts it this way: “The concept of lifetime employment is now a thing of the past. Everyone should accept this.”