HR country report: India in a state of transition

- HRM Asia Newsroom

- Topics: Employee Experience, Employment Law, Features, India

From South Korea to Australia, HRM Asia delves into the specific issues keeping HR awake at night in key Asia-Pacific markets as part of our Country Reports series.

In the next part of our report on India, we look at three industries that are rapidly being disrupted.

At a general election rally in the Uttar Pradesh city of Agra in November 2013, then-Indian Prime Ministerial candidate Narendra Modi told a packed crowd that his Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) would create 10 million new jobs during its first term in office.

In 2015, a year after he was elected, Modi launched the Skill India Mission with the goal of providing skills training to some 400 million Indians over the following seven years. He hoped to bring in more high-level jobs through this approach that would also make India “the world’s human resource capital”.

At that time, only 2% of India’s total workforce was made up of skilled workers, which is far lower than most other developing nations.

Twin blows

Today, Modi’s ambition of a steady job market remains more of a pipe dream than reality.

A government survey last year showed that things were nowhere near what he had hoped for back in 2015. Instead, India continues to be stricken by a severe skills shortage, caused by a multitude of both structural and cultural factors.

The Labour Ministry also admits that employment growth has been “sluggish”. This was its response to data from the official economic survey in 2016-17, which showed India’s unemployment rate had actually risen since 2014.

Total employment – the number of available jobs – in fact, fell across all sectors, according to an independent study by economist Vinoj Abraham.

Abraham noted that the falling employment levels were linked to a slowdown in overall economic growth, with growth in India’s Gross Domestic Product declining for six consecutive quarters between January 2016 and June 2017. The growth rate hit a three-year low of 5.7% in the second quarter of last year.

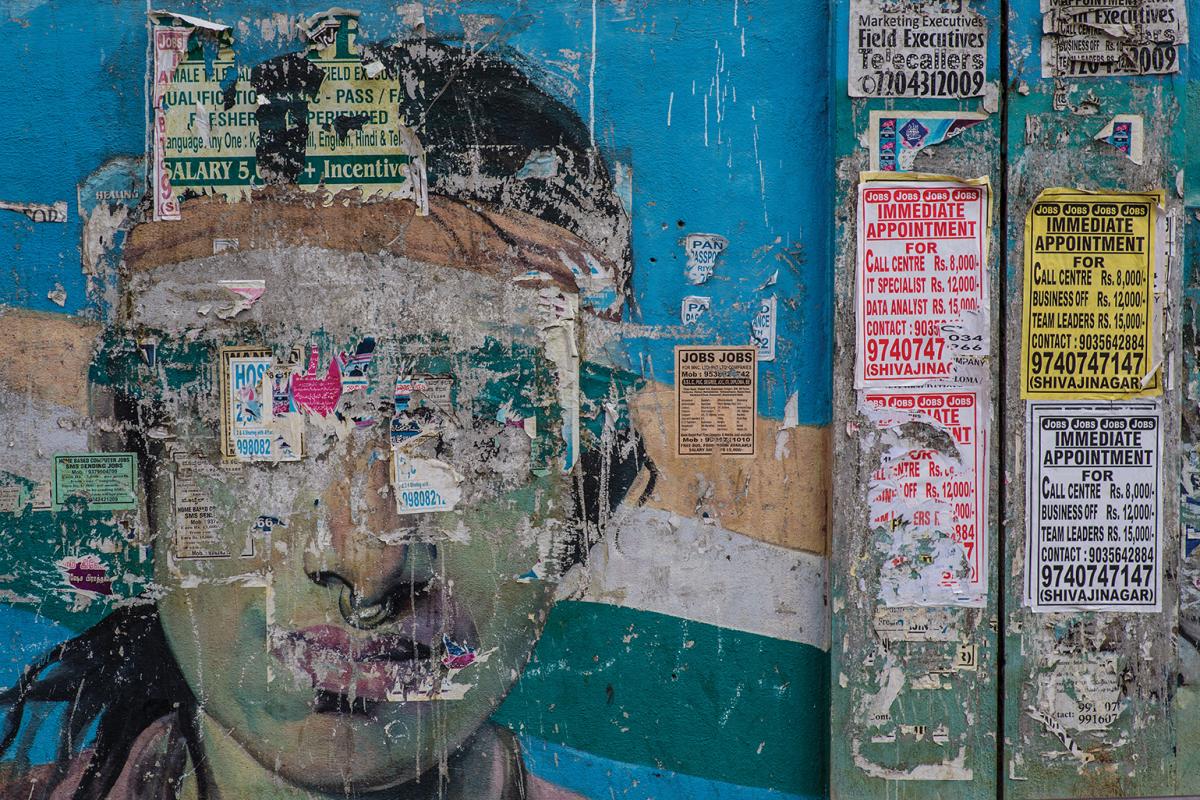

With an estimated 12 million Indians entering the workforce ever year until 2030, the country is simply not creating enough jobs for those newest entrants.

Experts attribute much of the market stagnation to two recent financial reforms: the demonetisation of all INR 500 (US$7.80) and INR 1,000 (US$15.60) banknotes at the end of 2016, and a new nationwide Goods and Services Tax (GST) that launched in July last year.

Former Prime Minister Manmohan Singh believes this “twin blow” has been “a complete disaster” for the national economy. “It has broken the back of our small businesses,” he said before the first anniversary of the sudden demonetisation policy in October last year.

That’s because demonetisation, in particular, has left millions of Indians exposed to increased uncertainty in employment, says Pawan Kumar, an Assistant Professor at Ramjas College at the University of Delhi.

He explains that this is because a majority of India’s workforce are employed in the informal sector, where most wage payments are made in cash form. Given the high proportion of those bank notes in circulation, demonetisation has affected informal workers the most.

According to The Financial Express, an estimated 482 million workers who earn cash incomes were expected to be affected in some shape or form.

Disruptive times

Local newspaper Economic Times’ online survey of 10,000 readers revealed that 45% believed demonetisation had reduced the number of jobs available in the short-term. Meanwhile, 23% believed the policy would have a negative, long-term impact on employment.

The situation is particularly dire for those in India’s IT industry – well-known as the country’s top-performing sector for much of the last few decades.

“The IT services industry is for sure weathering a storm, as the skill sets needed have changed along with the changes in the geopolitical situation,” Subhankar Roy Chowdhury, Executive Director, HR, Lenovo Asia-Pacific, tells HRM Magazine.

“This has had an impact on labour mobility.”

In the IT sector, digital disruption has meant analytics, machine learning, and other software skills related to artificial intelligence are now in high demand, making the hiring of people with these competencies a top priority.

Those skill sets, however, are still lacking across the country, despite its previous record in IT.

A 2016 Aspiring Minds survey of over 50,000 IT engineers in India found that 30% of respondents had difficulty answering even the most basic theoretical computer programming questions. Some 80% also failed to apply programming concepts to real-world situations.

Even more alarming was that fact that fewer than 5% of engineers were able to write compiler-friendly codes, or high-level programming languages that could be translated into simpler, non-abstract codes.

This emphasis on new skills has resulted in a significant number of layoffs, as was seen in last summer’s slash and burn exercises across major IT firms like IBM, Wipro, and Cognizant. Companies are now focused on removing redundancies, and replacing “passé” roles with new and more relevant job descriptions.

Stuck in low-tech work

Given the poor performance, many are now asking whose job it should have been to initiate the transformation? Is it the government, the industry as a whole, business leaders, or individuals themselves who should have stepped up?

The responsibility is not quite so clear cut. Experts note that a majority of Indians themselves – once at the top of the global IT tree – missed the opportunity to upskill in the face of emerging technologies and increasing digitalisation – particularly in the earlier part of this decade.

Companies were also slow to transform.

While India was once the technology hub of Asia, largely because of cost and scale factors, failure to adapt to digitalisation has meant it has become stuck in low-value technology work – such as system maintenance. The result has been that companies have been unable to produce the results today’s clients demand, gradually leading to a loss of business.

“Productising services and delivering higher quality is key,” Priya Chetty-Rajagopal, Executive Director, RGF Executive Search, told The Khaleej Times. “The big players, who are well aware of market dynamics, will now pay closer attention to clients’ needs, and move from maintenance to products.”

While the typical bread and butter projects will continue to exist, she says “companies have now realised a critical need for diversification”.

The problem then is not just about creating more jobs and pushing more skills training in India, but transforming both the attitudes of individuals and companies. Both groups need to truly seek out the needs of a changing economy – much like the rest of the world.

“The key to survival for companies and individuals is the same in this competitive market,” says Nihkil Shahane, HR Director at Technip India. Technical expertise will always be sought after, but individuals and entities must now demonstrate what differentiates them from the rest of the pack.

“The people with international experience, knowledge of certain technologies, multicultural experience, and adaptability to change will continue to thrive and succeed,” says Shahane.

“Not as scary as it sounds”

But Jaidip Chatterjee, India Country Head of HR at one of the country’s leading financial players, argues the current economic malaise need only be temporary.

“I strongly think it’s a phase which will subside and the labour market will be active (again) soon,” he tells HRM Magazine, citing a recent World Bank report that described India’s current decline as an “aberration”. He notes that the fall-back in economic growth has been largely due to interim policy disruptions in preparation for the new GST.

Chatterjee even disputes the sentiment that there is a lack of jobs, particularly outside the IT sector.

“When we look around at the hiring in the financial services industry or fast-moving consumer goods space, it is not as scary as it sounds,” he says.

He is “immensely hopeful” about India’s future, and that the economy will grow faster in 2018.

“It’s a matter of time before the recovery starts. I am hopeful that the new package of measures that the government intends to unveil will lead to generation of employment both in the private and public sectors,” he says.

Still, Chatterjee cautions that people will only succeed in the new world if they constantly upgrade and upskill themselves to add value to their enterprises.

Lenovo’s Chowdhury says there are still some ways to go before a complete transformation takes place.

“It’s not easy for an economy to transition to build skills overnight, but the government, academic institutions, and corporate entities have been making efforts,” he says.

For now, the reality remains at least for the moment, that no one can “rule out the possibility of organisations shedding skills not in demand,” Shahane says. “But at the same time, companies will be looking to hire niche talent that would provide them an edge over their competition.

“It is a tough situation to be in, but one that you cannot avoid.”

HR caught in the middle

HR in India is facing an unenviable task – with responsibility to not only facilitate skills training, but also handle redundancies and improve bottom lines when those skills mismatch. Still, there are some stories of particularly painful HR interactions now emerging from South Asia.

One former Tech Mahindra IT employee says he was given two choices when the company sought to restructure: resign by 10am the following day and be paid his basic salary, or be sacked with no compensation at all.

That employee recorded the exchange with HR, and later posted the audio online.

“Cost optimisation is happening at the company and your name is part of that list,” he was told. “If you can put in papers we will be treating it as a normal exit. If not, we will be sending you a termination letter.”

The HR manager added that there was “no flexibility” in the decision.

Shortly after the audio went viral, Tech Mahindra CEO CP Gurnani issued an apology via Twitter: “I deeply regret the way the employee discussion was done. We have taken the right steps to ensure it doesn’t repeat in the future.”

Grace under pressure

But should HR be excused for simply doing its job, and doing it the only way it knew?

Not at all, according to Kishore Shivdasani, the former CEO of Air India.

“Whilst one appreciates the fact that the HR executive was doing her job, it is obvious that she hadn’t been trained on how to terminate the services of an employee,” he wrote in an online response to the recording. “(There is a) total lack of grace, diplomacy, and understanding of the company’s reputation.”

Whether HR had to fire one or 1,000 individuals that day was unimportant because “the capability of managing employer-employee relationships must form an integral part of the terms and conditions of an HR executive’s service contract,” Shivdasani added.

Nihkil Shahane, HR Director at Technip India, is sympathetic to the cost objectives of businesses today, but agrees that tact and communication should never be overlooked.

“HR professionals must show empathy and respect to employee needs and counsel them as required,” he says.