Building learning agility across an organisation: The three Cs

- HRM Asia Newsroom

Practitioners believe that learning agility is a crucial thing to deal with the escalating dynamics and uncertainty of the business world. Therefore, at least in the last 10 years, many practitioners have tried to cultivate learning agility in their organisations, making it one of the key criteria in selecting or developing a leader.

It must be noted that there is not yet a sound framework to develop learning agility. However, if we return to the basic understanding of learning agility, we might discover the basic principles to foster it.

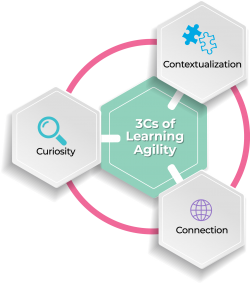

Exploring the word of “agility” itself gives us two key words: speed in understanding something, and flexibility in moving from one idea to another. On the other hand, the learning process itself is fundamentally indivisible from the process of building memory, which has three stages: encoding, storage, and retrieving. By connecting the understanding of agility with the basic learning process, we get three principles to build learning agility.

Exploring the word of “agility” itself gives us two key words: speed in understanding something, and flexibility in moving from one idea to another. On the other hand, the learning process itself is fundamentally indivisible from the process of building memory, which has three stages: encoding, storage, and retrieving. By connecting the understanding of agility with the basic learning process, we get three principles to build learning agility.

Curiosity

People can have a faster and more effective learning process, if within that process they connect new things to their previous comprehension. If the retrieving process will affect the speed of learning, then the accumulation of previous knowledge can be one of the foundations of learning agility.

But on the other hand, a profound accumulation of one thing can actually make someone hesitant to move to another idea or perspective. That is the reason information is ideally accumulated in a wide and varied manner, not a deep and uniform way. Curiosity is the starting point for hoarding information and knowledge like this. Therefore, we must ensure that our leadership style or organisational system does not hinder or even kill this curiosity.

Connection

The ability to connect something new with what is already present is very important for learning agility. Without this pattern recognition capability, the information and knowledge gathered will only be puzzle pieces that do not mean much on their own. Pattern recognition generally relies more on correlation but alas, this is not enough. Connecting requires understanding causation, and not only correlation. This understanding of cause and effect will help someone to comprehend something faster and more precisely. Furthermore, causal connections involving more elements of information or knowledge will help a person to think more broadly, building greater opportunities for them to think more flexibly.

Contextualisation

Learning agility is needed to deal with change – the capability to apply something to the new context is critical. A connection that is based merely on the correlations will potentially mislead without the right context, and it is a stronger understanding of causality that will help people to have the right contextualisation.

These simple principles can actually epitomise the understanding of learning agility that at this point in time is still quite diverse. Some currently see learning agility as an ability; while others see it more on the motivation dimension. Others still see it from the point of view of cognitive processes and behaviours. Curiosity is a part of the motivational dimension of learning agility. Connection and contextualisation are elements of cognitive process in learning agility. And because the cognitive process is something that can be built, learned and developed, then these two things are also a form of ability.

About the author

Deddi Tedjakumara is executive director of Prasetiya Mulya’s Executive Learning Institute. For more information on learing agility and the Prasetiya Mulya approach to business study, head to: http://www.pmeli.ac.id/.